Similar Diseases Without Atopy

Similar Diseases Without Atopy

Whether the same disease causes infantile eczema without positive skin test results or intrinsic asthma with its nasal equivalent is not entirely certain. There are a great many similarities.

Atopy Canadian Pharmacy

Where allergic asthma is common, intrinsic asthma is common and visa versa. An example is the high rate of asthma in the isolated community on the island of Tristan da Cunha where 74% of asthma cases were extrinsic and 26% were intrinsic. The intrinsic asthma picture is clouded by a fairly large group of patients with earlier symptoms of atopy who become more chronically asthmatic, develop sinus disease, and behave more and more like persons in the intrinsic group. The onset of purely intrinsic asthma in adults can be quite sudden, and it is often chronic and severe from the start. Women in their childbearing years are particularly susceptible, and lung autoantibodies have been found. It joins the list of diseases involving autoantibodies that develop more commonly in women, with the immunologic changes of pregnancy and the postpartum period. Autoantibodies also have been found in persons with infantile eczema without atopy.

One curious finding in patients with aspirin-sensitive asthma, which is usually intrinsic, is that the herpes drug acyclovir, an inhibitor of DNA polymerase, reduces bronchial inflammation and protects against a reaction to aspirin. Does the antiviral effect have anything to do with this or do other pharmacologic effects cause this phenomenon?

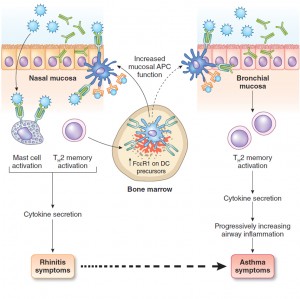

Atopic respiratory symptoms may develop soon after positive skin test results occur or not for several years, as if some other event may be required for localization of the disease. A follow-up of university students tested and questioned as freshmen, and questioned again about symptoms 4 years later as seniors, gives a good example showing the variable latency period between the development of positive skin test results and the development of symptoms. Very occasionally, symptoms develop before positive skin test results occur, perhaps because of local IgE production. In the same university student population that was observed 23 years after their original testing as freshmen, both hay fever and strongly positive skin test results raised the rate of future asthma to about 10% compared with 3% in alumnae with neither previous hay fever nor positive skin test results. Thus, beyond childhood the risk for new asthma was small even for the atopic population. Although the 10% occurrence of asthma in those with previous hay fever or positive skin tests seems a low risk, half of those who developed asthma had previous atopy or hay fever. Thus, atopy remained a substantial risk factor.